on

Clojure

We are going to explore Clojure by creating a fun project together. In particular, we will create a twitter bot that creates its text based on a mashup of Edward Lear’s poetry, and a goodly selection of functional programming text taken from Wikipedia.

Why Edward Lear and Functional Programming? First, because I really enjoy his poetry. I fondly remember reading his poetry to my children. Some of my favorite poems are The Pobble Who Has No Toes, The Quangle Wangle’s Hat, and The Jumblies. The whimsical nature of his poetry, like his contemporary Lewis Carroll, have great appeal to me. It is only natural that I should want to combine it with my other love, functional programming. In fact, I feel that some of of terms in functional programming like monad and functor, could fit right in with Edward Lear’s Nonsense Songs. This humble bot aims to unite the spheres of functional programming and nonsense poetry.

This tutorial will start with getting started with a basic Clojure project and editor. Then, we’ll build up our tweet generator with a Markov Chain. Finally, we will deploy our code to Heroku and hook it up to a twitter account, where it will live and tweet all on its own.

Since this walk through is geared to explain how I work in particular, we will start my essential ingredient to any coding project … tea. I brew myself a cup of PG Tips tea with a splash of milk, then I sit down and fire up my trusty editor Emacs.

Emacs is a lifestyle

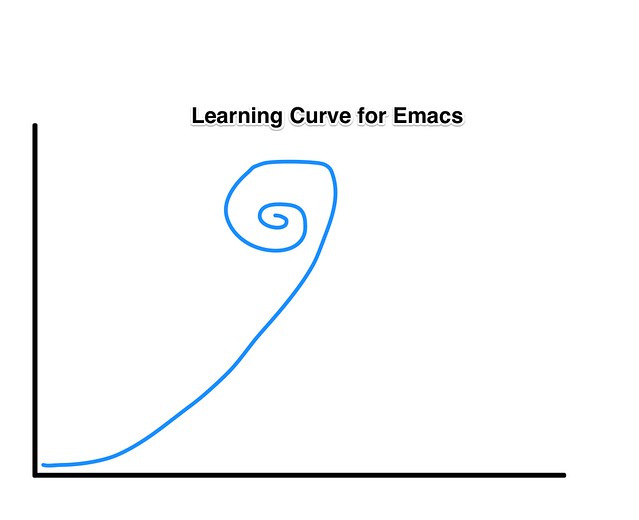

Emacs is more than an editor, it is a lifestyle. I also admit that the learning curve is steep. I actually only know about 4% of Emacs. This is completely normal given that the learning curve for the editor looks like a squiggly curlicue.

Nevertheless, once I started using Emacs for Clojure and experienced the interactive nature of the code and the REPL, (Read Eval Print Loop), I was hooked. I use a customized version of Emacs Starter Kit. I also find the Solarized Color-scheme a must for my eyes. For Clojure code, I use Cider for Emacs, which gives me the incredible interactive code experience that I was mentioning. If you are looking to try out Emacs I would recommend getting the starter kit and grabbing a good tutorial like this one.

Now that we have our tea and Emacs editor open, It is time to actually get our Clojure project created. For this I use Leiningen.

Getting the basic project setup

As we go through the walkthrough, feel free to reference the full source code on github.

Leiningen helps you create, manage, and automate your Clojure project. If you don’t already have Leiningen installed, follow the install instructions and download it. We are going to call our project markov-elear, so to create a project we just type the lein new command at our prompt:

lein new markov-elear

This will create a basic project skeleton for us to work with. Next, cd into the directory.

cd markov-elear

The default src file that it creates is src/markov_elear/core.clj. This is the first thing to change. We want a more meaningful file name. For our purposes, let’s rename it to src/markov_elear/generator.clj.

mv src/markov_elear/core.clj src/markov_elear/generator.clj

There is also a skeleton test file that is created in test/markov_elear/core_test.clj. We will want to do the same thing to it as well.

mv test/markov_elear/core_test.clj test/markov_elear/generator_test.clj

Next, open up the generator.clj file in Emacs. It has been created with the Leiningen template, so there is code already there that looks like:

(ns markov-elear.core)

(defn foo

"I don't do a whole lot."

[x]

(println x "Hello, World!"))

Since we changed our file to be named generator.clj, we also need to change the namespace to match it. Let’s also get rid of the foo function. It should now look like:

(ns markov-elear.generator)

Go ahead and open up the test file as well test/markov_elear/generator_test.clj. It also has some sample code in it from the Leiningen template. It looks like:

(ns markov-elear.core-test

(:require [clojure.test :refer :all]

[markov-elear.core :refer :all]))

(deftest a-test

(testing "FIXME, I fail."

(is (= 0 1))))

Change the namespace in the test to match the filename as well as the require to be that of markov-elear-generator.

(ns markov-elear.generator-test

(:require [clojure.test :refer :all]

[markov-elear.generator :refer :all]))

(deftest a-test

(testing "FIXME, I fail."

(is (= 0 1))))

At this point, we should now be able to run lein test from the command prompt and see our sample test fail.

lein test markov-elear.generator-test

lein test :only markov-elear.generator-test/a-test

FAIL in (a-test) (generator_test.clj:7)

FIXME, I fail.

expected: (= 0 1)

actual: (not (= 0 1))

Ran 1 tests containing 1 assertions.

1 failures, 0 errors.

Tests failed.

Fantastic. Our project is all set up. We are ready to jack-in with Emacs and Cider and start coding.

Cider Jack In and Experiment

Here is where we start to use the interactive nature of Clojure and Emacs in earnest. With the generator.clj file open in Emacs, type M-x cider-jack-in.

This will start a nREPL server for our project, so we can actively start to experiment with our code. This early stage is a bit like playing with putty before sculpting. It allows

us to quickly try out different approaches and get a feel for data constructs to use. For example, first put your cursor after the namespace form and hit C-x C-e to evaluate the form.

(ns markov-elear.generator)

You are now all set to the generator namespace for your evaluation.

Next, type into generator.clj the line:

(+ 1 1)

At this point, you can put your cursor at the end of the form and again hit C-x C-e you will see the result 2 appear in the mini-buffer at the bottom of the screen.

Now, we are ready to experiment with Markov Chains. The first thing we need is some small example to play with. Consider the following text.

"And the Golden Grouse And the Pobble who"

To construct a Markov Chain, we need to transform this text into a chain of prefixes and suffixes. In Markov chains, the length of the prefix can vary. The larger the prefix, the more predictable the text becomes, while the smaller the prefix size, the more random. In this case, we are going to use a prefix size of 2. We want to break up the original text into chunks of two words. The suffix is the next word that comes after.

|Prefix | Suffix

| -------------|-------------

| And the | Golden

| the Golden | Grouse

| Grouse And | the

| And the | Pobble

| the Pobble | who

| Pobble who | nil

This table becomes a guide for us in walking the chain to generate new text. If we start at a random place in the table, we can generate some text by following some simple rules.

- Choose a prefix to start. Your result string starts as this prefix.

- Take the suffix that goes with the prefix. Add the suffix to your result string. Also, add the last word of the prefix to the suffix, this is your new prefix.

- Look up your new prefix in the table and continue until there is no suffix.

- The result string is your generated text.

From our table, let’s start with the prefix the Pobble.

- Our starting prefix is the Pobble. Our result string will be initialized to it.

- Look up the prefix in the table. The suffix that goes with it is who. Add the suffix to the result string. The new prefix is the last word from the prefix and the suffix. So the new prefix is Pobble who.

- Look up up the prefix in the table, the suffix is nil. This means we have reached the end of the chain. Our resulting text is the Pobble who.

Things get interesting when there is more than one entry for a prefix. Notice that And the is in the table twice. This means that there is a choice of what entry to use and what suffix. We can randomly choose which one to use in our Markov Chain walk. As a result, our text will be randomly generated. If start with the prefix And the we have different possibilities for the resulting text. It could be

- And the Pobble who

- And the Golden Grouse And the Pobble who

- And the Golden Grouse And the Golden Grouse And the Pobble who

- And the Golden Grouse And the Golden Grouse And the Golden Grouse And the Pobble who

- etc…

Since we could get into repeating chains, we should also put a terminating condition of the total length of our resulting text as well.

Now that we know the general idea of what we want to do, let’s start small and start experimenting.

Baby steps

First, let’s take our example text and put it into code to play with in the REPL.

(def example "And the Golden Grouse And the Pobble who")

;; -> #'markov-elear.core/example

Now, we are going to want to split up this text by spaces. This is a job for clojure.string/split.

(def words (clojure.string/split example #" "))

words

;; -> ["And" "the" "Golden" "Grouse" "And" "the" "Pobble" "who"]

We also need to divide up these words in chunks of 3. Clojure’s partition-all will be perfect for this. We are going to partition the word list in chunks of three.

(def word-transitions (partition-all 3 1 words))

word-transitions

;; -> (("And" "the" "Golden")

;; ("the" "Golden" "Grouse")

;; ("Golden" "Grouse" "And")

;; ("Grouse" "And" "the")

;; ("And" "the" "Pobble")

;; ("the" "Pobble" "who")

;; ("Pobble" "who")

;; ("who"))

This is nice, but we really need to get it into a word-chain format. Ideally it would a map with the prefixes as the key and then have a set of suffixes to choose from. So that the prefix of And the would look like

{["And" "the"]} #{"Pobble" "Golden"}

A map with the key being the vector of prefix words and the value being the set of suffixes.

We need to map through the list of word-transitions and build this up somehow. Perhaps merge-with will help us out.

(merge-with concat {:a [1]} {:a [3]})

;; -> {:a (1 3)}

merge-with will allow us to combine the prefixes with multiple suffixes in a map form, but we really want it in a set. Time to experiment some more.

(merge-with clojure.set/union {:a #{1}} {:a #{2}})

;; -> {:a #{1 2}}

Yes, that will do nicely. Let’s try this out in a reduce over the word-transitions.

(reduce (fn [r t] (merge-with clojure.set/union r

(let [[a b c] t]

{[a b] (if c #{c} #{})})))

{}

word-transitions)

;; {["who" nil] #{},

;; ["Pobble" "who"] #{},

;; ["the" "Pobble"] #{"who"},

;; ["Grouse" "And"] #{"the"},

;; ["Golden" "Grouse"] #{"And"},

;; ["the" "Golden"] #{"Grouse"},

;; ["And" "the"] #{"Pobble" "Golden"}}

Tangible turn to tests

We have been experimenting in the REPL, but now that we have a feel for where we are going it is time to write some tests.

I really like to use the lein-test-refesh plugin. It will continually rerun the tests whenever we change something in our files. I find the feedback loop is much faster then running lein test alone. It also takes care of reloading all the namespaces for you, so I don’t run into problems where my REPL environment gets out of sync with my code. To add it to your project, simply add the following to your project.clj file.

:profiles {:dev {:plugins [[com.jakemccrary/lein-test-refresh "0.7.0"]]}}

Now, you can start it up from your prompt by running

lein test-refresh

First, let’s get rid of the sample test and replace it with a real one. We want this test to be about the word chain that we were experimenting with.

Building the Word Chain

Add this to your generator_test.clj file.

(ns markov-elear.generator-test

(:require [clojure.test :refer :all]

[markov-elear.generator :refer :all]))

(deftest test-word-chain

(testing "it produces a chain of the possible two step transitions between suffixes and prefixes"

(let [example '(("And" "the" "Golden")

("the" "Golden" "Grouse")

("And" "the" "Pobble")

("the" "Pobble" "who"))]

(is (= {["the" "Pobble"] #{"who"}

["the" "Golden"] #{"Grouse"}

["And" "the"] #{"Pobble" "Golden"}}

(word-chain example))))))

As you save the file, you will notice the test failing in your lein test-refresh window. This is because we haven’t written the word-chain function yet. After all of our experimentation, we know exactly what we need to do. Add the following function to your generator.clj file.

(defn word-chain [word-transitions]

(reduce (fn [r t] (merge-with clojure.set/union r

(let [[a b c] t]

{[a b] (if c #{c} #{})})))

{}

word-transitions))

Your test should now pass.

What about generating the word chain from an string of text? When we were experimenting in the REPL, we saw that using parition-all was going to be useful. Let’s add a test for that now in generator_test.clj. We want to parse an input string that has spaces or new lines.

(deftest test-text->word-chain

(testing "string with spaces and newlines"

(let [example "And the Golden Grouse\nAnd the Pobble who"]

(is (= {["who" nil] #{}

["Pobble" "who"] #{}

["the" "Pobble"] #{"who"}

["Grouse" "And"] #{"the"}

["Golden" "Grouse"] #{"And"}

["the" "Golden"] #{"Grouse"}

["And" "the"] #{"Pobble" "Golden"}}

(text->word-chain example))))))

To make it pass, add the text->word-chain function in the generator_test.clj.

(defn text->word-chain [s]

(let [words (clojure.string/split s #"[\s|\n]")

word-transitions (partition-all 3 1 words)]

(word-chain word-transitions)))

Now that we have our word-chain, we are going to need a way to walk the chain, given a beginning prefix, and come up with our resulting text.

Random Walking the Chain

Going back to our test file generator_test.clj, add a new test for a walk-chain function that we want:

(deftest test-walk-chain

(let [chain {["who" nil] #{},

["Pobble" "who"] #{},

["the" "Pobble"] #{"who"},

["Grouse" "And"] #{"the"},

["Golden" "Grouse"] #{"And"},

["the" "Golden"] #{"Grouse"},

["And" "the"] #{"Pobble" "Golden"}}]

(testing "dead end"

(let [prefix ["the" "Pobble"]]

(is (= ["the" "Pobble" "who"]

(walk-chain prefix chain prefix)))))))

Given a the starting prefix of ["the" "Pobble"], it will walk our chain until it reaches the a dead end of there

being no more suffixes. The result should be ["the" "Pobble" "who"].

Going back to our generator.clj file, we can start constructing a function to do this

(defn walk-chain [prefix chain result]

(let [suffixes (get chain prefix)]

(if (empty? suffixes)

result

(let [suffix (first (shuffle suffixes))

new-prefix [(last prefix) suffix]]

(recur new-prefix chain (conj result suffix))))))

It takes the prefix and get the suffixes associated with it. If there are no suffixes, it terminates and returns the result.

Otherwise, it uses shuffle to pick a random suffix. Then it constructs the new prefix from the last part of the current prefix and the suffix. Finally, it recurs into the function using the new-prefix and adding the suffix to the result.

We have another passing test, but we still need to consider the other walking of the chain where it has a choice. Go ahead and add a test for that now too.

(deftest test-walk-chain

(let [chain {["who" nil] #{},

["Pobble" "who"] #{},

["the" "Pobble"] #{"who"},

["Grouse" "And"] #{"the"},

["Golden" "Grouse"] #{"And"},

["the" "Golden"] #{"Grouse"},

["And" "the"] #{"Pobble" "Golden"}}]

(testing "dead end"

(let [prefix ["the" "Pobble"]]

(is (= ["the" "Pobble" "who"]

(walk-chain prefix chain prefix)))))

(testing "multiple choices"

(with-redefs [shuffle (fn [c] c)]

(let [prefix ["And" "the"]]

(is (= ["And" "the" "Pobble" "who"]

(walk-chain prefix chain prefix))))))))

Because we have randomness to deal with, we can use with-redefs to redefine shuffle to always return the original collection for us. We also need to deal with repeating chains. We will have to give it another termination condition, like a word or character length for termination. Since our bot is destined for twitter, a 140 char limit seems reasonable.

(deftest test-walk-chain

(let [chain {["who" nil] #{},

["Pobble" "who"] #{},

["the" "Pobble"] #{"who"},

["Grouse" "And"] #{"the"},

["Golden" "Grouse"] #{"And"},

["the" "Golden"] #{"Grouse"},

["And" "the"] #{"Pobble" "Golden"}}]

(testing "dead end"

(let [prefix ["the" "Pobble"]]

(is (= ["the" "Pobble" "who"]

(walk-chain prefix chain prefix)))))

(testing "multiple choices"

(with-redefs [shuffle (fn [c] c)]

(let [prefix ["And" "the"]]

(is (= ["And" "the" "Pobble" "who"]

(walk-chain prefix chain prefix))))))

(testing "repeating chains"

(with-redefs [shuffle (fn [c] (reverse c))]

(let [prefix ["And" "the"]]

(is (> 140

(count (apply str (walk-chain prefix chain prefix)))))

(is (= ["And" "the" "Golden" "Grouse" "And" "the" "Golden" "Grouse"]

(take 8 (walk-chain prefix chain prefix)))))))))

Note: The test will actually run forever since it is stuck in an endless loop. You will have to restart your test-refresh session after you implement the solution.

Adjusting our generator.clj, we first need a helper function that will turn our result chain into a string with spaces, so that we can count the chars and make sure that they are under the limit. We will call it chain->text.

(defn chain->text [chain]

(apply str (interpose " " chain)))

It takes a chain like ["And" "the" "Pobble" "who"] and gives us back the display text.

(chain->text ["And" "the" "Pobble" "who"])

;; -> "And the Pobble who"

Now we can add the char limit counting to our walk-chain function.

(defn chain->text [chain]

(apply str (interpose " " chain)))

(defn walk-chain [prefix chain result]

(let [suffixes (get chain prefix)]

(if (empty? suffixes)

result

(let [suffix (first (shuffle suffixes))

new-prefix [(last prefix) suffix]

result-with-spaces (chain->text result)

result-char-count (count result-with-spaces)

suffix-char-count (inc (count suffix))

new-result-char-count (+ result-char-count suffix-char-count)]

(if (>= new-result-char-count 140)

result

(recur new-prefix chain (conj result suffix)))))))

We check the result-char-count and the chosen suffix-char-count before we recur, so that we can ensure that

it doesn’t go over 140 chars. If it is going to go over the limit, we return the result and do not recur.

What we need now is another higher level function that, when given a prefix and a word chain, will return the resulting text.

Taking A Start Text Phrase, Walking the Chain, and Returning Text.

Going back to the generator_test.clj file, let’s go ahead and write the test. We will use with-redefs again to control our randomness.

(deftest test-generate-text

(with-redefs [shuffle (fn [c] c)]

(let [chain {["who" nil] #{}

["Pobble" "who"] #{}

["the" "Pobble"] #{"who"}

["Grouse" "And"] #{"the"}

["Golden" "Grouse"] #{"And"}

["the" "Golden"] #{"Grouse"}

["And" "the"] #{"Pobble" "Golden"}}]

(is (= "the Pobble who" (generate-text "the Pobble" chain)))

(is (= "And the Pobble who" (generate-text "And the" chain))))))

To make the test pass in our generator.clj file, we create the function that will take a start-phrase as a prefix and a word chain.

Then it will split the start-phrase by spaces, so that it will match up to our prefix keys. Next, it will use walk-chain to get the resulting text chain. Finally, it will turn the result text chain into plain text with chain->text.

(defn generate-text

[start-phrase word-chain]

(let [prefix (clojure.string/split start-phrase #" ")

result-chain (walk-chain prefix word-chain prefix)

result-text (chain->text result-chain)]

result-text))

Taking a moment to recap, this is what we have so far:

- We can take string, parse it and turn it into a word chain.

- We can take an input phrase and word chain and generate some new text by taking a random walk in the chain.

What we are missing is a way to train our bot, by reading in some files of text and building out the chain that it will walk.

Training the bot by reading input files

To train our bot, we need to be able to give it a text file and have it turn it into a word chain. Our first text selection will be from The Quangle Wangle’s Hat.

Making it easier on ourselves, we will do some slight formatting of the text. Save it in a file called resources/quangle-wangle.txt.

On the top of the Crumpetty Tree

The Quangle Wangle sat,

But his face you could not see,

On account of his Beaver Hat.

For his Hat was a hundred and two feet wide,

With ribbons and bibbons on every side,

And bells, and buttons, and loops, and lace,

So that nobody ever could see the face

Of the Quangle Wangle Quee.

The Quangle Wangle said

To himself on the Crumpetty Tree,

"Jam, and jelly, and bread

Are the best of food for me!

But the longer I live on this Crumpetty Tree

The plainer than ever it seems to me

That very few people come this way

And that life on the whole is far from gay!"

Said the Quangle Wangle Quee.

But there came to the Crumpetty Tree

Mr. and Mrs. Canary;

And they said, "Did ever you see

Any spot so charmingly airy?

May we build a nest on your lovely Hat?

Mr. Quangle Wangle, grant us that!

O please let us come and build a nest

Of whatever material suits you best,

Mr. Quangle Wangle Quee!"

And besides, to the Crumpetty Tree

Came the Stork, the Duck, and the Owl;

The Snail and the Bumble-Bee,

The Frog and the Fimble Fowl

(The Fimble Fowl, with a Corkscrew leg);

And all of them said, "We humbly beg

We may build our homes on your lovely Hat,--

Mr. Quangle Wangle, grant us that!

Mr. Quangle Wangle Quee!"

And the Golden Grouse came there,

And the Pobble who has no toes,

And the small Olympian bear,

And the Dong with a luminous nose.

And the Blue Baboon who played the flute,

And the Orient Calf from the Land of Tute,

And the Attery Squash, and the Bisky Bat,--

All came and built on the lovely Hat

Of the Quangle Wangle Quee.

And the Quangle Wangle said

To himself on the Crumpetty Tree,

"When all these creatures move

What a wonderful noise there'll be!"

And at night by the light of the Mulberry moon

They danced to the Flute of the Blue Baboon,

On the broad green leaves of the Crumpetty Tree,

And all were as happy as happy could be,

With the Quangle Wangle Quee.

We can now use clojure.java.io/resource to open the file and slurp to turn it into a string. From there, we can simply use our text->word-chain function to transform it into the word chain that we need. Add the process-file function to the generator.clj file and give it a try in the REPL.

(defn process-file [fname]

(text->word-chain

(slurp (clojure.java.io/resource fname))))

(generate-text "And the" (process-file "quangle-wangle.txt"))

;; -> "And the Attery Squash, and the Bumble-Bee,

;; The Frog and the Bisky Bat,-- All came and built on the

;; Crumpetty Tree

;; The plainer than ever it"

Great! We just need to add some more text files. We will add some more Edward Lear Poems, As well as some text from wikipedia on Functional Programming.

- The Project Gutenberg eBook, Nonsense Books, by Edward Lear

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monad_(functional_programming)

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Functional_programming

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clojure

After we have chosen our text selections, we define a list of input files and the final chain that is the result of all the processed text.

(def files ["quangle-wangle.txt" "monad.txt" "clojure.txt" "functional.txt"

"jumblies.txt" "pelican.txt" "pobble.txt"])

(def functional-leary (apply merge-with clojure.set/union (map process-file files)))

Giving it a try in the REPL.

(generate-text "On the" functional-leary)

;; -> "On the broad green leaves of the list. Under lazy evaluation,

;; the length function will return a new monadic value.

;; The bind operation takes"

Now we are having fun :)

Artistic tweaking

Here is when it turns to artistic tweaking. I want to hand select a few entry prefixes, so that the text generated will tend to start out sounding like Edward Lear and have functional text mixed in.

(def prefix-list ["On the" "They went" "And all" "We think"

"For every" "No other" "To a" "And every"

"We, too," "For his" "And the" "But the"

"Are the" "The Pobble" "For the" "When we"

"In the" "Yet we" "With only" "Are the"

"Though the" "And when"

"We sit" "And this" "No other" "With a"

"And at" "What a" "Of the"

"O please" "So that" "And all" "When they"

"But before" "Whoso had" "And nobody" "And it's"

"For any" "For example," "Also in" "In contrast"])

Also, I want to fix a bit of the punctuation of the generated text. In particular, I want to trim the text to the last punctuation in the text. Then, if it ends in a comma, I want to replace it with a period. If there is no punctuation, I want to drop the last word and add a period. I also want to clean up an quotes that get escaped in the text.

Adding a test for that in our generator_test.clj file:

(deftest test-end-at-last-puntcuation

(testing "Ends at the last puncuation"

(is (= "In a tree so happy are we."

(end-at-last-punctuation "In a tree so happy are we. So that")))

(testing "Replaces ending comma with a period"

(is (= "In a tree so happy are we."

(end-at-last-punctuation "In a tree so happy are we, So that"))))

(testing "If there are no previous puncations, just leave it alone and add one at the end"

(is ( = "In the light of the blue moon."

(end-at-last-punctuation "In the light of the blue moon there"))))

(testing "works with multiple punctuation"

(is ( = "In the light of the blue moon. We danced merrily."

(end-at-last-punctuation "In the light of the blue moon. We danced merrily. Be"))))))

We can make this test pass in our generator.clj file, by using some string and regex functions.

(defn end-at-last-punctuation [text]

(let [trimmed-to-last-punct (apply str (re-seq #"[\s\w]+[^.!?,]*[.!?,]" text))

trimmed-to-last-word (apply str (re-seq #".*[^a-zA-Z]+" text))

result-text (if (empty? trimmed-to-last-punct)

trimmed-to-last-word

trimmed-to-last-punct)

cleaned-text (clojure.string/replace result-text #"[,| ]$" ".")]

(clojure.string/replace cleaned-text #"\"" "'")))

Using this, we can now make a tweet-text function that will randomly choose a prefix from our prefix list and generate our mashup text.

(defn tweet-text []

(let [text (generate-text (-> prefix-list shuffle first) functional-leary)]

(end-at-last-punctuation text)))

(tweet-text)

;; -> "With a wreath of shrimps in her short white hair.

;; And before the end of this period Hickey sent an email

;; announcing the language Hope."

Alright, that last one made me smile.

We now have a function that will generate tweets for us. The next step is to hook it up to a Twitter account so that we can share our smiles with the world.

Hooking the bot up to Twitter

To hook up our bot to twitter, you need to create a twitter account. Once you do that, need to do the following:

- Go to https://apps.twitter.com/ to create new twitter application. You will want to set the permission so that it can post to the twitter account. This will give you a Consumer Key (API Key) and a Consumer Secret (API Secret).

- Go to the the Keys and Access Tokens section of the application. On the bottom half there is a button that says Create my access token, click it. It will generate two more key pieces of information for you: Access Token and Access Token Secret.

Please note that these setting are sensitive and should not be checked into github or shared publicly. To help make our twitter account access, we are going to need the help of two libraries. The first is twitter-api that will help us make our api calls. The second is environ that will help us keep our login information safe.

Add both libraries to your project.clj

[twitter-api "0.7.8"]

[environ "1.0.0"]

Also add the lein-environ plugin to your project.clj as well.

:plugins [[lein-environ "1.0.0"]]

The environ plugin allows us to pass configuration information from environment settings or a profiles.clj file that can be ignored and not checked in. Let’s go ahead and add a profiles.clj file to the root of our project and put in all our twitter account info.

Danger: Do not check in your twitter keys and push to a public repo!

{:dev {:env {:app-consumer-key "foo"

:app-consumer-secret "bar"

:user-access-token "foo2"

:user-access-secret "bar2"}}}

Also add both the twitter-api and the environ library to the project namespace in the generator.clj file.

(ns markov-elear.generator

(:require [twitter.api.restful :as twitter]

[twitter.oauth :as twitter-oauth]

[environ.core :refer [env]]))

This will allow us to define my-creds that will make our creditionals for our twitter app.

(def my-creds (twitter-oauth/make-oauth-creds (env :app-consumer-key)

(env :app-consumer-secret)

(env :user-access-token)

(env :user-access-secret)))

Now that we can talk to our twitter account. We can finally write a status-update function that will post our markov chain generated text.

(defn status-update []

(let [tweet (tweet-text)]

(println "generated tweet is :" tweet)

(println "char count is:" (count tweet))

(when (not-empty tweet)

(try (twitter/statuses-update :oauth-creds my-creds

:params {:status tweet})

(catch Exception e (println "Oh no! " (.getMessage e)))))))

Giving it a try:

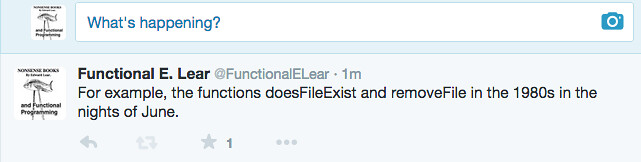

(status-update)

;; -> {.... :text "For example, the functions doesFileExist and

;; removeFile in the 1980s

;; in the nights of June."}}

Hooray! We are almost there. We next need a way to run this status update on a periodic basis, having it post automatically for us.

Automating our tweets

To have this run from the command line in an automated fashion, we are going to do two things. The first is to use the Overtone at-at library for scheduling. And the other thing that we need to do is to add a main function to the generator.clj file and to setup up the project so that it can run with lein trampoline run.

So first, modify the project.clj file to have the at-at library, as well as the main function for the namespace.

:dependencies [[org.clojure/clojure "1.6.0"]

[overtone/at-at "1.2.0"]

[twitter-api "0.7.8"]

[environ "1.0.0"]]

:main markov-elear.generator

:min-lein-version "2.0.0"

:plugins [[lein-environ "1.0.0"]]

:profiles {:dev {:plugins [[com.jakemccrary/lein-test-refresh "0.7.0"]]}})

Then, going back to the generator.clj file, first add the overtone/at-at library to the namespace. Then, define a pool for the scheduling process, and add in a -main function to tweet for us every 8 hours.

(ns markov-elear.generator

(:require [overtone.at-at :as overtone]

[twitter.api.restful :as twitter]

[twitter.oauth :as twitter-oauth]

[environ.core :refer [env]]))

(def my-pool (overtone/mk-pool))

(defn -main [& args]

;; every 8 hours

(println "Started up")

(println (tweet-text))

(overtone/every (* 1000 60 60 8) #(println (status-update)) my-pool))

Now we should be able to try this from the command line.

lein trampoline run

and see something like the following

Started up

Are the best of food for me!

generated tweet is : With only a beautiful pea-green veil Tied with a flumpy sound.

char count is: 62

{... :text With only a beautiful pea-green veil Tied with a flumpy sound.}

At this point our program is complete. We could happily leave it running locally. It is much better though, to deploy it somewhere. http://heroku.com/ is a fantastic place for this. It provides free hosting and has nice Clojure support.

Deploying to Heroku

The first thing you will need to do is to create an account on Heroku. It is free of charge. You can create your login at https://signup.heroku.com/dc.

Next, you will need the Heroku Toolbelt. This gives you a nice command line tool to configure and deploy applications. You can download it from https://devcenter.heroku.com/articles/getting-started-with-clojure#set-up.

Once you have downloaded the tool, you will need to configure it with your username and password. You can do this at the command line by typing heroku login. You will be prompted for your email and password.

-> heroku login

Enter your Heroku credentials.

Email:

Password:

Now you are all set to configure your project.

If you haven’t initialized it yet as a git repo, do so with

git init

After that, we need to tell Heroku how to start up our app. We do this with a Procfile in the main project directory. Go ahead and add the file with the following contents.

worker: lein trampoline run

This will tell Heroku to run our program as a background worker, (rather than a web app), and start it up with lein trampoline run.

The next step is to create an app on Heroku for it. This will get Heroku ready to receive your code for deployment.

Type heroku create into your command prompt at the root of the project. You will see.

-> heroku create

Creating calm-reaches-2803... done, stack is cedar-14

https://calm-reaches-2803.herokuapp.com/ | https://git.heroku.com/calm-reaches-2803.git

Git remote heroku added

It created a random application name for you, (which you can rename later through the console). It also added a repository called heroku to our git config. Once we push our code here, it will automatically deploy.

You will also need to setup your Twitter creditionals on the Heroku account so it will be able to talk to it. You can do this with heroku config.

You need to do a command line heroku config for each one of our configurations:

heroku config:set APP_CONSUMER_KEY=foo

heroku config:set APP_CONSUMER_SECRET=bar

heroku config:set USER_ACCESS_TOKEN=foo2

heroku config:set USER_ACCESS_SECRET=bar2

Finally, we can push all of our changes to Heroku with:

git push heroku master

You should see it deploy and tweet for you!

If you need to check the logs, you can do it with heroku logs.

We have successfully created and deployed a markov bot that will tweet for us. Let’s recap what we have done so far.

Summary

- Use Emacs REPL integration to play and experiment with the code. This is what I call an early sculpting with code phase, or REPL Driven Development.

- As soon as we have a good idea where we are headed, switch into a more Test Driven Development cycle with the lein-test-refresh plugin.

- Create the core of our code to generate and walk our Markov Chain.

- Create ways to parse input text files to train our bot on.

- Artistically select some entry points into our chain using prefixes. Also artistically, fix up the puncuation of the resulting text.

- Set up a Twitter account.

- Use the environ library to handle our environment specific twitter configuration.

- Use the twitter-api library to talk to the twitter account

- Use the at-at library to schedule a job periodically to tweet for us.

- Deploy the application to Heroku.

I hope you have enjoyed our Clojure bot creating journey. The full code for this project can be found at https://github.com/gigasquid/markov-elear. The twitter bot lives at functionalELear

I encourage you to experiment and create your own art bots and, of course, to continue to explore and enjoy the wonderful world of Clojure.

Special thanks to Jake McCrary and Paul Henrich for reviewing this post and providing wonderful feedback.